This article will provide you with all the info you need when hunting with stone arrowheads.

Stone projectile points have been in use for hundreds of thousands of years and I’ve been hunting with them exclusively for over 25 years. There’s a lot of misinformation regarding their effectiveness and some states have even outlawed their use for hunting. Unfortunately these laws are based on conjecture and bias and not hard facts. The information included here is based on my years of research as an archaeologist, primitive archery enthusiast and a primitive bowhunter with over two decades of experience using primitive weapons in real hunting scenarios.

Flint blades can match modern surgical scalpels in sharpness and are unsurpassed for cutting and butchering tasks. Flint is the best material to tip projectiles with if you want to bring down big game quickly. Flint spearpoints and arrow points kept our ancestors fed and clothed for millennia, and the fact that we’re still here is living proof these materials work. I’ve conducted numerous penetration tests with stone points on freshly killed deer and the results proved that well-made flint hunting points made by experienced knappers are just as sharp and penetrate just as well as modern steel broadheads.

However, the one striking difference between modern broadheads and prehistoric stone arrow points is their size. Today’s steel arrowheads are much larger than the stone points used in prehistory. Tiny stone arrow points were used across North America and tiny flint blades called microliths were used throughout Europe. Though thousands of years and thousands of miles separated these people, how and why did they come to such a parallel in technology?

I believe small arrow points were used for one reason: penetration. Native people weren’t, for the most part, using bows pulling 60+ pounds. They were incredibly skilled hunters who knew their business and were able to get close to game while remaining undetected. Powerful bows were unnecessary at that range, and they also affected the hunter’s ability to draw slowly and make an accurate shot when the animal was that close. Prehistoric hunters were generally smaller than we are and therefore didn’t have as long a draw or shoot powerful bows like we do today. Their focus was shot placement, and lighter bows excel in close-range hunting scenarios.

The arrows of prehistory were, in some cases, much lighter than the wooden arrows we shoot today and therefore carried less momentum. To make up for this and achieve adequate penetration, ancient people shrunk the size of their arrow points to tiny dimensions. Mistakenly called “bird points” by collectors, it wasn’t until recently that scientists were able to test these tiny points for minute traces of blood proteins still preserved on their surfaces. The results shocked the experts. These points often had blood proteins from large game like Cervid (deer and elk), Ovis (Bighorn sheep) and sometimes even Ursus (bear), indicating that these tiny points were actually used on large game.

Tiny stone points allow lighter arrows to achieve lethal penetration even when launched from light poundage bows. My own penetration tests on freshly killed deer using a 40-lb bow and lightweight 300 grain reed arrows tipped with tiny stone points prove this seemingly underpowered combination has no problem penetrating to the far side of the chest wall on a deer. Incredibly, some of the “bird points” even shattered the offside ribs.

Weaker weapons have another hidden advantage: greater accuracy at close range. A lighter bow has a smooth, effortless draw, making pinpoint accuracy much easier in close-range hunting scenarios. Generations of ancient hunting knowledge steered arrow technology toward smaller stone points that left narrow, deep wound channels as opposed to larger stone points that gave wider, shallower wound channels. If small stone points were ineffective they would have been abandoned long ago. But the frequency at which they are found on archaeological sites throughout North America and other continents is proof they worked in a variety of environments and on a variety of game animals. That’s a lesson I pay close attention to. I’ve used small stone point technology on my own arrows and have never been disappointed. From small grey squirrels to heavily muscled whitetail deer, small stone points have proved their lethality every time.

Our more powerful bows and heavier wooden shafts carry more momentum and are capable of deeper penetration than the lighter arrows of the past. However, stone points still have thicker cross sections that incur more resistance than a flat steel point. Modern bowhunters should follow the lessons of ancient hunters and use smaller stone points whenever possible. When purchasing my stone hunting points, I strongly suggest choosing the smallest point you can legally use. Some of my personal hunting points only weigh 15 or 20 grains, yet they’ve proved just as lethal as larger broadheads. If you need a 125 grain point for your arrows to achieve perfect flight, I suggest adding a hardwood footer or foreshaft of heavier wood to the front of the arrow so flight is perfect before adding the stone point.

Stone isn’t nearly as heavy as steel and a 125 grain stone point will be much too large for an arrow today. Stone and steel points are different in every aspect. You can’t force stone points to fit the mold of a modern steel broadhead and expect identical performance. Adjustments have to be made. Ancient hunters learned this long ago. They discovered that large stone arrowpoints achieve very poor penetration, so they made them smaller to compensate. Back then hunting was a matter of life or death and their survival was based on the effectiveness of their weapons. Remember that. Follow the lessons of our ancestors and use smaller, lighter points whenever possible. I have, and they’ve never let me down.

To see firsthand what small stone points are capable of, watch this video where I test the penetration of tiny stone points by clicking here.

Another common question concerns the durability of stone points. Muscle tissue and soft, vital organs pose no threat to a stone point. The serrated edges easily slice through soft tissue and open some ghastly wounds. In addition, the ribs of deer-sized game are not as hard as you might think. Flint arrowheads have no problem getting past them and penetrating into the vitals. Careful autopsies performed on every animal I’ve killed with flint points proves they are durable, lethal, and just as effective as modern steel broadheads. Usually a small chip off the very tip is the only damage they suffer. Sometimes small nicks are taken off corners or basal ears, though it’s usually very minor and only a few seconds of repair will make them usable again. Other times there’s no damage and the point is reusable. My penetration tests also revealed another hidden advantage of smaller points: they’re much more likely to slip between ribs on entry. Smaller points sometimes nick entrance ribs, but have never hit a rib dead center, and once inside they often penetrate to the far side of the chest wall. They are more likely to strike offside ribs as opposed to those on entrance. But by then the point has already done its deadly work and that animal won’t be traveling very far.

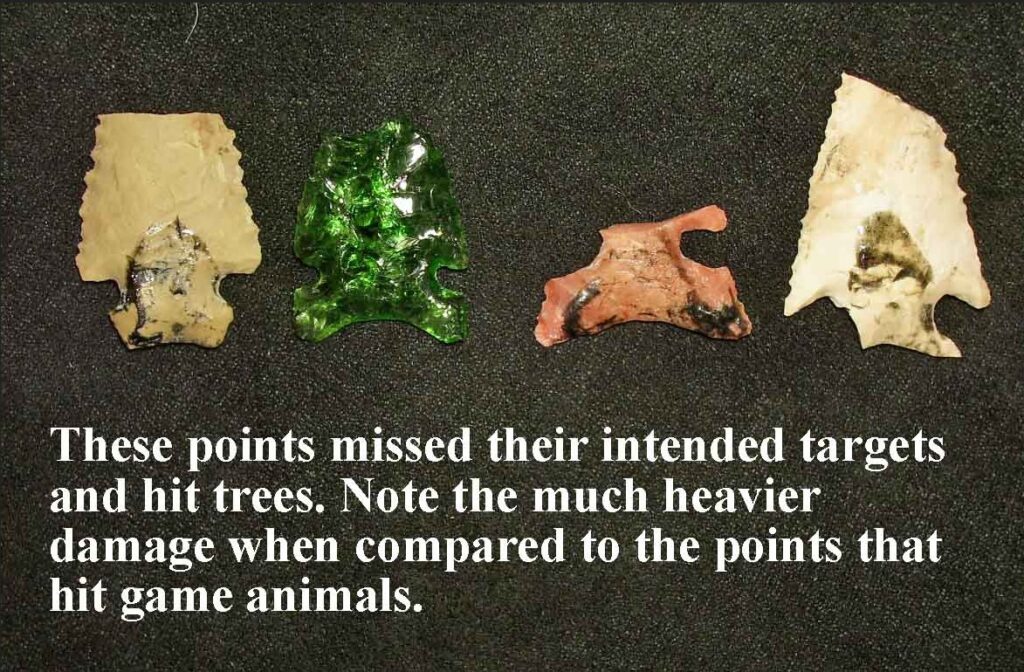

Now if you miss your target then all bets are off. Trees and rocks are much less forgiving and will usually damage flint arrowheads, sometimes severely. Hitting such objects usually results in shattered tips, sheared edges, and sometimes even pulverized points where only the very base of the point remains in the haft. Such impacts will usually damage stone points beyond repair. Sometimes, however, they will surprise you and can be chiseled out of tree trunks and rotten logs with little or no damage.

If the point hits sandy soil then damage is usually minimal, though sand is very abrasive and will significantly dull the edges of the stone point. It’s a good idea to have a small, sharp pressure flaker and little leather pad with you so dull points can be resharpened in the field. Points that hit soft dirt and clay will usually be undamaged, though the edges should be checked for sharpness and should be resharpened by taking very small chips off the edge if there’s any question.

I’m very particular about protecting the edges of my hunting points and you should be too. Stone points are very sharp, but they’re also brittle and need protection to preserve the lethal edges. Don’t jam stone tipped arrows into a back quiver and allow them to bang against each other or they will dull very quickly. Needle sharp tips are easily broken. Edges that were razor sharp will become dull and harmless. Don’t let that happen. Always protect your stone points with a wrapping of toilet paper that’s held in place with a twist-tie or small rubber band. I only remove the protective coverings when I’m hunting. That preserves the sharp edges until the moment of truth arrives.